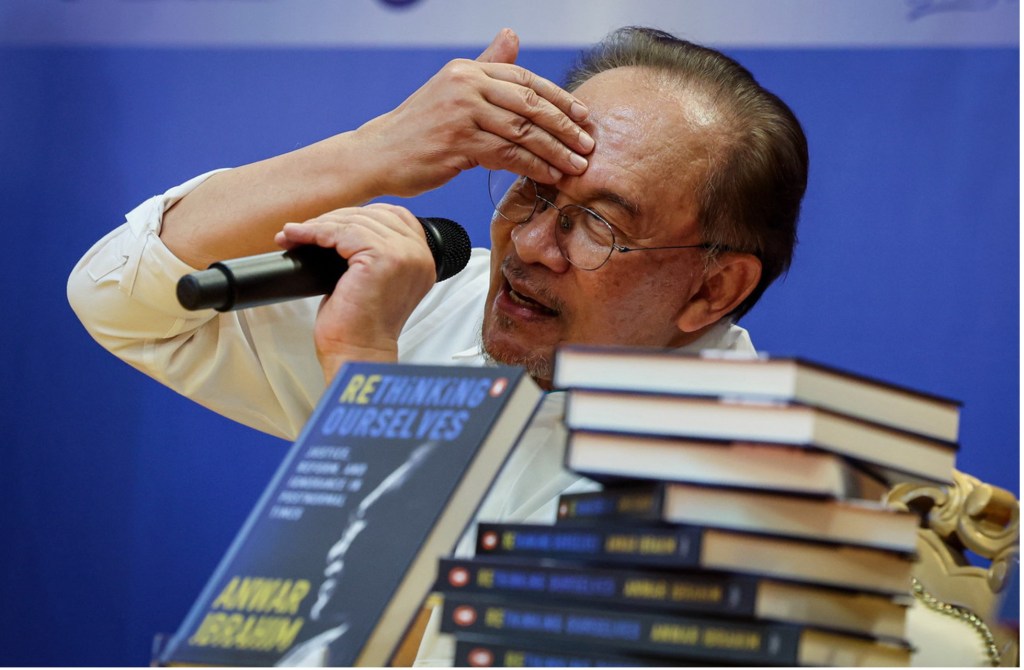

[1] Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim recently launched his latest book, Rethinking Ourselves: Justice, Reform and Ignorance in Postnormal Times. The book explores the role of government and society in an increasingly turbulent age, along with issues of justice and power, corruption and impunity, democracy and pluralism. Drawing upon philosophy, history, his years in prison and his observations of Malaysian politics and society, Anwar argues that we must rethink ourselves if we are to better navigate the rapid changes reshaping the world.

[2] The Anwar in the book emerges as a leader shaped by injustice – a man for whom prison strengthened his convictions and sharpened his purpose. Few will quarrel with the philosophical thrust of his argument or his call for fighting corruption, overhauling the education system or the urgency of reforms to save Malaysia from rot, racism and ruin. His plea for moral and intellectual renewal – to transcend ignorance, uphold justice and build inclusive societies – is also long overdue.

[3] The book has been hailed as a significant contribution to contemporary political thought, a timely book for our turbulent age, a book that sets Anwar apart from his contemporaries. “Were all political leaders as well-read and thoughtful as this one,” wrote one reviewer. Perhaps no other Malaysian prime minister has received such accolades.

[4] But while the world may marvel at his philosophical insights, Malaysians will insist on viewing his thesis from a domestic perspective. And here the contradictions come into sharp relief. For all his eloquence and learned musings, the lofty ideas of his book have found little expression in practice at home.

[5] Anwar is not merely a public intellectual meditating on the disorders of the age; he is a sitting prime minister with the authority and mandate to translate ideas into policy. As prime minister, he does not have the luxury of simply ruminating about reform; he must implement it, match rhetoric with action and display the courage of conviction. And this is precisely where he repeatedly disappoints.

[6] Consider corruption – an issue he himself placed at the centre of his political project. While some modest improvements have been made, his refusal to hold close allies like Zahid Hamidi accountable has rendered his anti-corruption rhetoric hollow. And for all his indignation over 1MDB, he quietly pressed for a pardon for Najib Razak, the man at the heart of the scandal. Other cases – Sabah being a notable example – have simply been allowed to fade from view for political reasons.

[7] What use is pontificating about Asian values when we ourselves remain mired in corruption, unable to come to terms with our multicultural identity and endlessly distracted by the politics of race and religion? He calls for a new globally inclusive synthesis – one that “genuinely promotes good society and a just and sustainable world order” – yet has done little to foster it at home.

[8] Philosophical musings have their place, of course, but the more germane question is why the reforms he references in his book — judicial independence, clean governance, a fair economy, strengthening democracy and respect for diversity — remain conspicuously unfulfilled more than three years into his term?

[9] When push came to shove, he chose power over principle, coalition arithmetic over reform and political convenience over moral clarity. Anwar the thinker is animated by philosophy, history and ideas; Anwar the politician appears driven by raw ambition and power at any cost. He did not rupture the old order as he once vowed to do; he accommodated himself to it.

[10] The tragedy is not merely that he failed to deliver reform but that he failed at the one moment when reform was still possible. He had the power and the mandate, the institutions were malleable, expectations were high – and yet he shrank from the task. His supporters may continue to write paeans to his intellect and moral vision, but history will not be moved by flattery. It will ask a simpler, sterner question: what did he actually change?

[11] In the end, the book merely confirms the view that we have in Anwar a prime minister who is simply unable to live up to his own rhetoric. It leaves us with the disquieting conclusion that the man who emerges from the pages of Rethinking Ourselves is not the same man we see in Putrajaya; one of them is a fabrication.

[12] If anyone needs to rethink himself, it is Anwar. And we, too, must rethink the indulgence we have extended to him for far too long, lest we become complicit in our own disappointment.

[Dennis Ignatius |Kuala Lumpur |18 January 2026]

You must be logged in to post a comment.